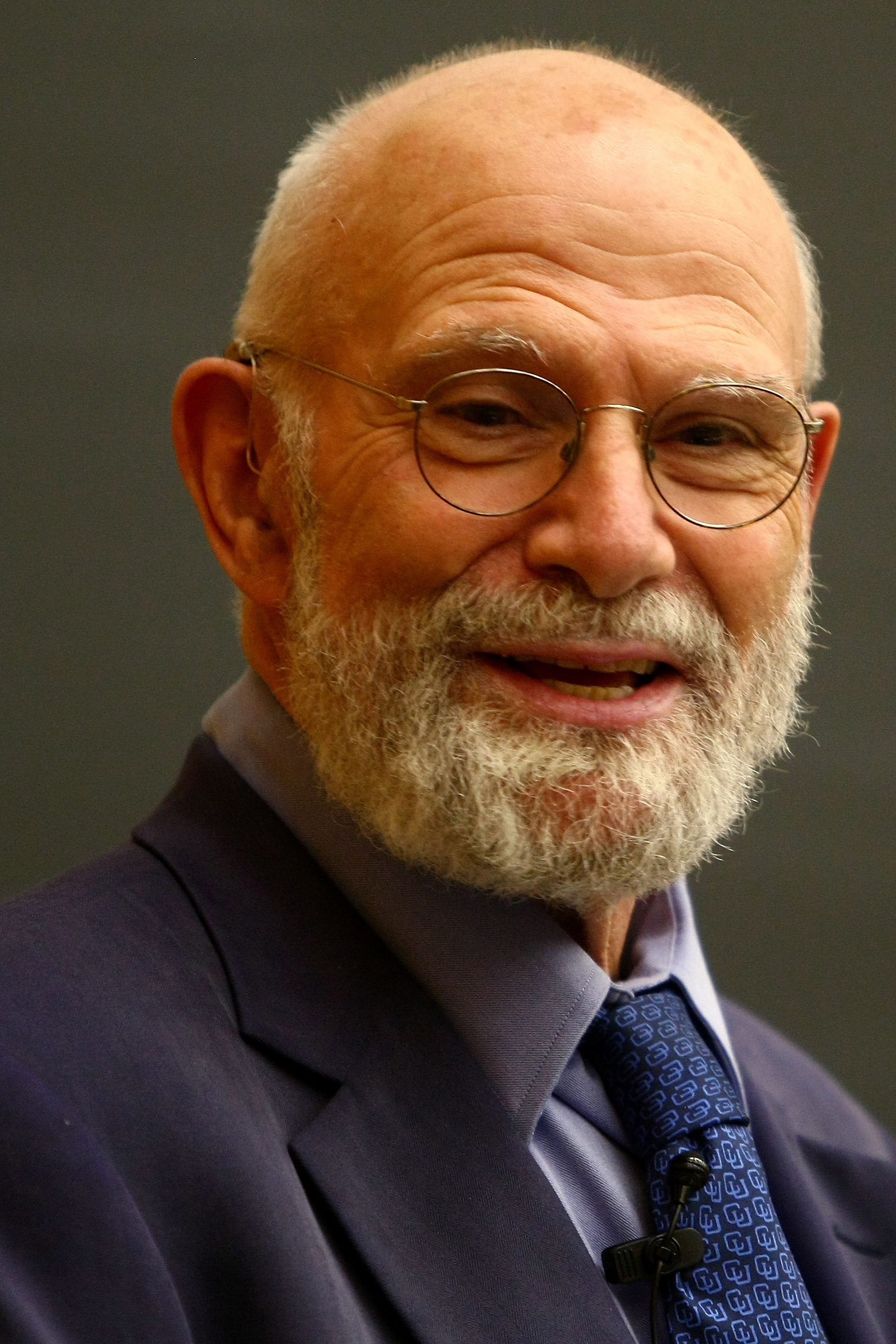

My decision to move to New York more than a year later really had nothing to do with Oliver, and I certainly did not have a relationship in mind. There was an entire country between us, not to mention 30 years’ age difference.

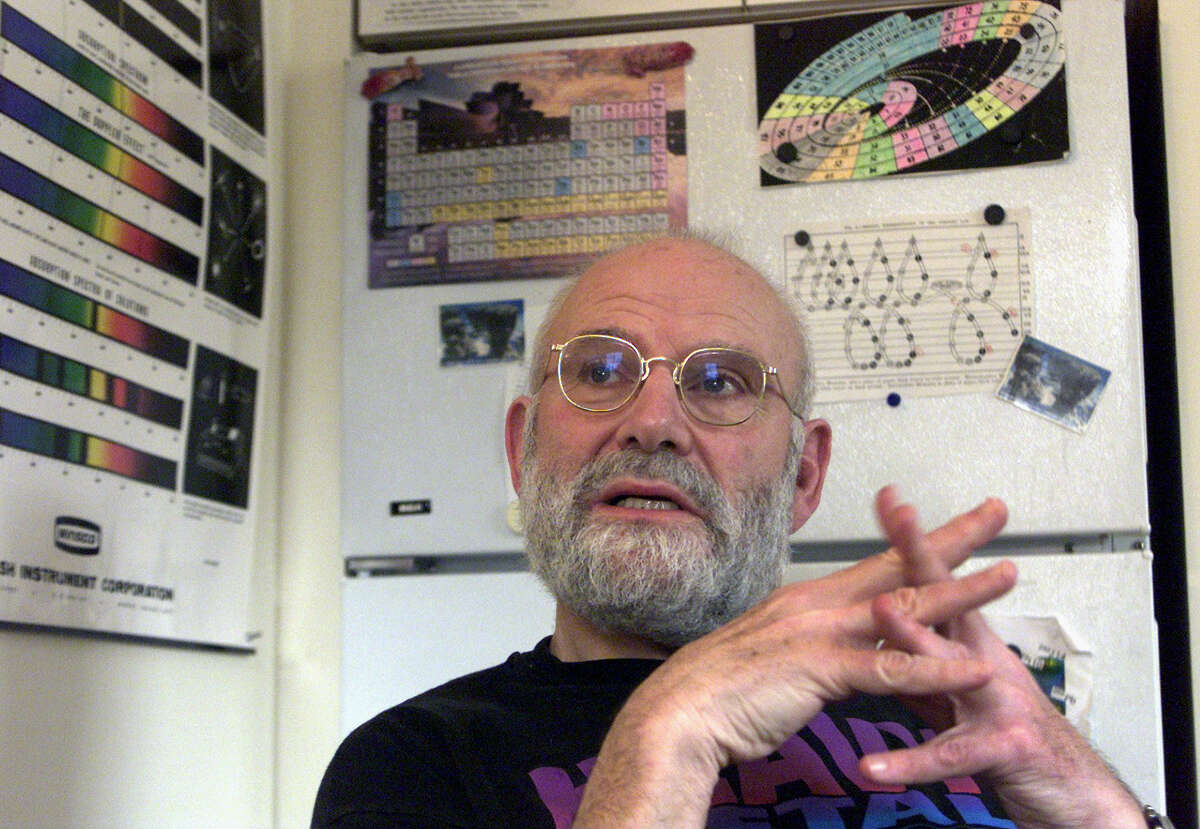

“I am reminded of how Nabokov compared winter trees to the nervous systems of giants,” he wrote back.Įven so, that was that – for then. With his neurologist’s eye, he felt they looked like neurons. I thought they looked like vascular capillaries. I sent him photographs I had taken in Central Park of bare tree limbs. I remember how O got quite carried away talking about 19th-century medical literature, “its novelistic qualities” – an enthusiasm I shared. How could one not be? He was brilliant, sweet, modest, handsome, and prone to sudden, ebullient outbursts of boyish enthusiasm. But I did know that I was intrigued and attracted. By the end of our lunch, I hadn’t come to any firm conclusions on either matter, as he was both very shy and quite formal – qualities I do not possess. I had not known – had never considered – whether he was hetero- or homosexual, single or in a relationship.

(“It was understood at an early age that one could not sleep without sedation,” he told me wryly.) We found we had something other than writing in common: he, too, was a lifelong insomniac – indeed, from a family of insomniacs. We lingered at the table, talking, well into the afternoon. We had lunch at a cafe across the street from his office: mussels, fries, and several rounds of dark Belgian beer. Thus, a correspondence between O and me began.Ī month later, I happened to be in New York and, at Oliver’s invitation, paid a visit.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)